(Adding categories) |

m (Updating categories: added Quadrupedal) |

||

| (156 intermediate revisions by 35 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Plagiarized}}{{Taxobox |

||

| − | {{Tabber}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | {{Italic title}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | {{Taxobox |

||

| + | | image = 661E2C62-EE75-40DE-BB44-D61EAC2A630B.jpeg |

||

| − | | name = [[File:Parasaurolophusname.png]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | | image = Tumblr_f222041f030850ae155ab1e8109baf70_986589a8_1280.png |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| image_width = 240px |

| image_width = 240px |

||

| − | | |

+ | | domain = [[Eukarya|Eukaryota]] |

| − | | |

+ | | regnum = [[Animalia]] |

| + | | phylum = [[Chordata]] |

||

| ordo = †[[Ornithischia]] |

| ordo = †[[Ornithischia]] |

||

| subordo = †[[Ornithopoda]] |

| subordo = †[[Ornithopoda]] |

||

| familia = †[[Hadrosauridae]] |

| familia = †[[Hadrosauridae]] |

||

| − | | tribus = |

+ | | tribus = †Parasaurolophini |

| genus = †'''''Parasaurolophus''''' |

| genus = †'''''Parasaurolophus''''' |

||

| − | | genus_authority = |

+ | | genus_authority = Parks, 1922 |

| type_species = {{extinct}}'''''Parasaurolophus walkeri''''' |

| type_species = {{extinct}}'''''Parasaurolophus walkeri''''' |

||

| type_species_authority = Parks, 1922 |

| type_species_authority = Parks, 1922 |

||

| subdivision_ranks = Referred species |

| subdivision_ranks = Referred species |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | | subdivision = |

||

| − | *{{extinct}}'''''Parasaurolophus |

+ | *{{extinct}}'''''Parasaurolophus tubicen''''' <small>(Wiman, 1931)</small> |

| ⚫ | |||

*{{extinct}}'''''Parasaurolophus walkeri''''' <small>(Parks, 1922)</small> |

*{{extinct}}'''''Parasaurolophus walkeri''''' <small>(Parks, 1922)</small> |

||

and [[Parasaurolophus#Species|see text]]. |

and [[Parasaurolophus#Species|see text]]. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | | synonyms = |

||

| ⚫ | |||

and [[Parasaurolophus#Species|see text]]. |

and [[Parasaurolophus#Species|see text]]. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| − | '''''Parasaurolophus''''' (pronounced /[[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|ˌpærəsɔˈrɒləfəs]]/ [[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|PARR-ə-saw-ROL-ə-fəs]], commonly also /[[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|ˌpærəˌsɔrəˈloʊfəs]]/ [[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|PARR-ə-SAWR-ə-LOH-fəs]]; meaning "near crested lizard" in reference to ''[[ |

+ | '''''Parasaurolophus''''' (pronounced /[[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|ˌpærəsɔˈrɒləfəs]]/ [[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|PARR-ə-saw-ROL-ə-fəs]], commonly also /[[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|ˌpærəˌsɔrəˈloʊfəs]]/ [[wikipedia:Parasaurolophus|PARR-ə-SAWR-ə-LOH-fəs]]; meaning "near crested lizard" in reference to ''[[Saurolophus]]''), commonly shortened as '''''Parasaur''''', is a genus of [[wikipedia:Ornithopod|ornithopod dinosaur]] from the [[Wikipedia:Late Cretaceous|Late Cretaceous Period]] of what is now North America, about 83-73 million years ago. It was a herbivore that walked both as a [[Wikipedia:Bipedilism|biped]] and a [[wikipedia:Quadruped|quadruped.]] Three species are recognized: ''P. walkeri'' (the type species), ''P. tubicen'', and the short-crested ''P. cyrtocristatus''. Remains are known from Alberta, Canada, and New Mexico and Utah, USA. It was first described in 1922 by [[wikipedia:William Parks|William Parks]] from a skull and partial skeleton in Alberta. |

| − | ''Parasaurolophus'' is a hadrosaurid |

+ | ''Parasaurolophus'' is a hadrosaurid (commonly referred to as Duck billed dinosaurs because of their mouths resembling the bills of waterfowl such as ducks) part of a diverse family of Cretaceous dinosaurs known for their range of bizarre head adornments. This genus is known for its large, elaborate cranial crest, which at its largest forms a long curved tube projecting upwards and back from the skull. ''[[wikipedia:Charonosaurus|Charonosaurus]]'' from China, which may have been its closest relative, had a similar skull and potentially a similar crest. The crest has been much discussed by scientists; the consensus is that major functions included visual recognition of both species and sex, acoustic resonance, and thermoregulation. It is one of the rarer duckbills, being known from only a handful of good specimens. |

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

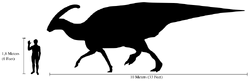

| − | [[File:Comparison;human¶saurolophus.png|thumb|250px]]As is the case with most dinosaurs, the skeleton of ''Parasaurolophus'' is incompletely known. The length of the [[wikipedia:Type specimen|type specimen]] of ''P. walkeri'' is estimated at 9.5 |

+ | [[File:Comparison;human¶saurolophus.png|thumb|250px]]As is the case with most dinosaurs, the skeleton of ''Parasaurolophus'' is incompletely known. The length of the [[wikipedia:Type specimen|type specimen]] of ''P. walkeri'' is estimated at 9.5 meters (31 ft). Its skull is about 1.6 meters (5.2 ft) long, including the crest, whereas the type skull of ''P. tubicen'' is over 2.0 meters (6.6 ft) long, indicating a larger animal.<ref name=LW42a>Lull, Richard Swann Wright, Nelda E. ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America'', page 229. Published: 1942, Geological Society of America, ''Geological Society of America Special Paper '''40'''''</ref> P. walkeri's weight is estimated at 3.6 tonnes (4 tons),P. tubicen is estimated to be 6.6 tonnes (7 tons) and P. cytocristatus ist estimated to be 12.6 tonnes (13 tons).single known forelimb was relatively short for a hadrosaurid, with a short but wide [[wikipedia:scapula|shoulder blade]]. The [[wikipedia:femur|thighbone]] measures 103 centimeters (3.38 ft) long in ''P. walkeri'' and is robust for its length when compared to other hadrosaurids.<ref name=LW42b>Lull and Wright, ''Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America'', pp. 209-213.</ref> The [[wikipedia:humerus|upper arm]] and [[wikipedia:pelvis|pelvic]] bones were also heavily built.<ref name=BC06>Brett-Surman, Michael K. and Wagner, Jonathan R. Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.) ''Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs'', chapter: ''Appendicular anatomy in Campanian and Maastrichtian North American hadrosaurids'', pages 135–169. Published, 2006, Indiana University Press, in Bloomington and Indianapolis ISBN 0-253-34817-X</ref> |

Like other hadrosaurids, it was able to walk on either two legs or four. It probably preferred to forage for food on four legs, but ran on two.<ref name=HWF04>Horner, John R., Weishampel, David B.; and Forster, Catherine A, Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; and Dodson, Peter (eds.) ''The Dinosauria'', 2nd edition, chapter: Hadrosauridae, pages 438-463. Published: 2004, University of California Press, in Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-24209-2</ref> The [[wikipedia:spinous process|neural spines]] of the [[wikipedia:Vertebra|vertebrae]] were tall, as was common in lambeosaurines;<ref name=LW42b/> tallest over the hips, they increased the height of the back. [[wikipedia:Integumentary system|Skin]] impressions are known for ''P. walkeri'', showing uniform tubercle-like scales but no larger structures.<ref name=WAP22>Parks, William A. ''Parasaurolophus walkeri'', a new genus and species of crested trachodont dinosaur, volume 13, pages 1-32. Published: 1922, University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series.</ref> |

Like other hadrosaurids, it was able to walk on either two legs or four. It probably preferred to forage for food on four legs, but ran on two.<ref name=HWF04>Horner, John R., Weishampel, David B.; and Forster, Catherine A, Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; and Dodson, Peter (eds.) ''The Dinosauria'', 2nd edition, chapter: Hadrosauridae, pages 438-463. Published: 2004, University of California Press, in Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-24209-2</ref> The [[wikipedia:spinous process|neural spines]] of the [[wikipedia:Vertebra|vertebrae]] were tall, as was common in lambeosaurines;<ref name=LW42b/> tallest over the hips, they increased the height of the back. [[wikipedia:Integumentary system|Skin]] impressions are known for ''P. walkeri'', showing uniform tubercle-like scales but no larger structures.<ref name=WAP22>Parks, William A. ''Parasaurolophus walkeri'', a new genus and species of crested trachodont dinosaur, volume 13, pages 1-32. Published: 1922, University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series.</ref> |

||

| − | The most noticeable feature was the cranial crest, which protruded from the rear of the head and was made up of the [[wikipedia:Premaxilla|premaxilla]] and [[wikipedia:Nasal bone|nasal bones]]. The ''P. walkeri'' type specimen has a notch in the neural spines near where the crest would hit the back, but this may be a [[wikipedia:Pathology|pathology]] peculiar to this individual.<ref name=LW42b/> William Parks, who named the genus, hypothesized that a ligament ran from the crest to the notch to support the head.<ref name=WAP22/> Although the idea seems unlikely,<ref name=DFG97/> ''Parasaurolophus'' is sometimes restored with a skin flap from the crest to the neck. |

+ | The most noticeable feature was the cranial crest, which protruded from the rear of the head and was made up of the [[wikipedia:Premaxilla|premaxilla]] and [[wikipedia:Nasal bone|nasal bones]]. The ''P. walkeri'' type specimen has a notch in the neural spines near where the crest would hit the back, but this may be a [[wikipedia:Pathology|pathology]] peculiar to this individual.<ref name=LW42b/> William Parks, who named the genus, hypothesized that a ligament ran from the crest to the notch to support the head.<ref name=WAP22/> Although the idea seems unlikely,<ref name="DFG97">Glut, Donald F. Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia, Chapter: ''Parasaurolophus'', pages 678–684. Published: 1997, McFarland & Co, in Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 0-89950-917-7</ref> ''Parasaurolophus'' is sometimes restored with a skin flap from the crest to the neck. |

The crest was hollow, with distinct tubes leading from each nostril to the end of the crest before reversing direction and heading back down the crest and into the skull. The tubes were simplest in ''P. walkeri'', and more complex in ''P. tubicen'', where some tubes were blind and others met and separated.<ref name=SW99>Sullivan, Robert M. and Williamson, Thomas E. A new skull of ''Parasaurolophus'' (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus, from the series ''New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin'', '''15''', pages 1-52. Published: 1999, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, in Albuqueque, New Mexico.</ref> While ''P. walkeri'' and ''P. tubicen'' had long crests with only slight curvature, ''P. cyrtocristatus'' had a short crest with a more circular profile.<ref name=JHO61>Ostrom, John H. 1961 ''A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of New Mexico'', Journal of Paleontology, Volume 35, 3rd issue, on pages 575–577.</ref> |

The crest was hollow, with distinct tubes leading from each nostril to the end of the crest before reversing direction and heading back down the crest and into the skull. The tubes were simplest in ''P. walkeri'', and more complex in ''P. tubicen'', where some tubes were blind and others met and separated.<ref name=SW99>Sullivan, Robert M. and Williamson, Thomas E. A new skull of ''Parasaurolophus'' (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus, from the series ''New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin'', '''15''', pages 1-52. Published: 1999, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, in Albuqueque, New Mexico.</ref> While ''P. walkeri'' and ''P. tubicen'' had long crests with only slight curvature, ''P. cyrtocristatus'' had a short crest with a more circular profile.<ref name=JHO61>Ostrom, John H. 1961 ''A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of New Mexico'', Journal of Paleontology, Volume 35, 3rd issue, on pages 575–577.</ref> |

||

| Line 56: | Line 53: | ||

''P. tubicen'', from New Mexico, is known from the remains of at least three individuals.<ref name=HWF04/> It is the largest species, with more complex air passages in its crest than ''P. walkeri'', and a longer, straighter crest than ''P. cyrtocristatus''.<ref name=SW99/> |

''P. tubicen'', from New Mexico, is known from the remains of at least three individuals.<ref name=HWF04/> It is the largest species, with more complex air passages in its crest than ''P. walkeri'', and a longer, straighter crest than ''P. cyrtocristatus''.<ref name=SW99/> |

||

| − | ''P. cyrtocristatus'', from New Mexico and Utah, is known from three possible specimens. It is the smallest species, with a short rounded crest.<ref name=SW99/> Its small size and the form of its crest have led several scientists to suggest that it represents juveniles or females of ''P. tubicen'', which is from roughly the same time and from the same formation in New Mexico. As noted by Thomas Williamson, the type material of ''P. cyrtocristatus'' is about 72% the size of ''P. tubicen'', close to the size at which other lambeosaurines are interpreted to begin showing definitive [[wikipedia:Sexuals dimorphism|sexual dimorphism]] in their crests (~70% |

+ | ''P. cyrtocristatus'', from New Mexico and Utah, is known from three possible specimens. It is the smallest species, with a short rounded crest.<ref name=SW99/> Its small size and the form of its crest have led several scientists to suggest that it represents juveniles or females of ''P. tubicen'', which is from roughly the same time and from the same formation in New Mexico. As noted by Thomas Williamson, the type material of ''P. cyrtocristatus'' is about 72% the size of ''P. tubicen'', close to the size at which other lambeosaurines are interpreted to begin showing definitive [[wikipedia:Sexuals dimorphism|sexual dimorphism]] in their crests (~70% of adult size).<ref name=TEW00/> This position has been rejected in recent reviews of lambeosaurines.<ref name=HWF04/><ref name=ER07/> In January 25, 2021, a well-preserved skull of Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus was founded and reveals the dinosaur evolution of bizarre crest. |

==Paleobiology== |

==Paleobiology== |

||

| − | ===Paleoecology=== |

||

| ⚫ | ''Parasaurolophus walkeri'', from the [[wikipedia:Dinosaur Park Formation|Dinosaur Park Formation]], was a member of a diverse and well-documented fauna of prehistoric animals, including well-known dinosaurs such as the [[wikipedia:ceratopsidae|horned]] ''[[wikipedia:Centrosaurus|Centrosaurus]]'', ''[[Styracosaurus]]'', and ''[[Chasmosaurus]]''; fellow duckbills ''[[wikipedia:Prosaurolophus|Prosaurolophus]]'', ''[[ |

||

| − | |||

The New Mexican species shared their environment with the duckbill ''[[wikipedia:Kritosaurus|Kritosaurus]]'', horned ''[[wikipedia:Pentaceratops|Pentaceratops]]'', armored ''[[wikipedia:Nodocephalosaurus|Nodocephalosaurus]]'', ''[[wikipedia:Saurornitholestes|Saurornitholestes]]'', and currently unnamed tyrannosaurids.<ref name=WETAL04/> The Kirtland Formation is interpreted as river floodplains appearing after a retreat of the Western Interior Seaway. Conifers were the dominant plants, and [[wikipedia:Ceratopsidae|chasmosaurine]] horned dinosaurs were apparently more common than hadrosaurids.<ref name=DAR89>Russell, Dale A. ''An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America'', 1989. Publisher: NorthWord Press, in Minocqua, Wisconsin. ISBN 1-55971-038-1 Pages 160–164.</ref> |

The New Mexican species shared their environment with the duckbill ''[[wikipedia:Kritosaurus|Kritosaurus]]'', horned ''[[wikipedia:Pentaceratops|Pentaceratops]]'', armored ''[[wikipedia:Nodocephalosaurus|Nodocephalosaurus]]'', ''[[wikipedia:Saurornitholestes|Saurornitholestes]]'', and currently unnamed tyrannosaurids.<ref name=WETAL04/> The Kirtland Formation is interpreted as river floodplains appearing after a retreat of the Western Interior Seaway. Conifers were the dominant plants, and [[wikipedia:Ceratopsidae|chasmosaurine]] horned dinosaurs were apparently more common than hadrosaurids.<ref name=DAR89>Russell, Dale A. ''An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America'', 1989. Publisher: NorthWord Press, in Minocqua, Wisconsin. ISBN 1-55971-038-1 Pages 160–164.</ref> |

||

===Feeding=== |

===Feeding=== |

||

| − | As a hadrosaurid, ''Parasaurolophus'' was a large bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore, eating plants with a sophisticated skull that permitted a grinding motion analogous to chewing. Its teeth were continually replacing and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. It used its beak to crop plant material, which was held in the jaws by a cheek-like organ. Feeding would have been from the ground up to around 4 |

+ | As a hadrosaurid, ''Parasaurolophus'' was a large bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore, eating plants with a sophisticated skull that permitted a grinding motion analogous to chewing. Its teeth were continually replacing and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. It used its beak to crop plant material, which was held in the jaws by a cheek-like organ. Feeding would have been from the ground up to around 4 meters (13 feet) above.<ref name=HWF04/> As noted by [[wikipedia:Robert T. Bakker|Bob Bakker]], lambeosaurines have narrower beaks than hadrosaurines, implying that ''Parasaurolophus'' and its relatives could feed more selectively than their broad-beaked, crestless counterparts.<ref name=RTB86>Bakker, Robert T. 1986. ''The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction'', published by William Morrow, in New York. ISBN 0-8217-2859-8 Page 194.</ref> |

===Cranial crest=== |

===Cranial crest=== |

||

| Line 90: | Line 84: | ||

====Cooling function==== |

====Cooling function==== |

||

The large surface area and [[wikipedia:vascularization|vascularization]] of the crest also suggests a thermoregulatory function.<ref name=SW96>Sullivan, Robert M. and Williamson, Thomas E., 1996. A new skull of ''Parasaurolophus'' (long-crested form) from New Mexico: external and internal (CT scans) features and their functional implications, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 16, issue 3, Suppl. pp.68A.</ref> P.E. Wheeler first suggested this use in 1978 as a way keep the brain cool.<ref name=PEW78>Wheeler, P.E., 1978. ''Elaborate CNS cooling structure in large dinosaurs'' Journal of Nature, vol. 275, on pp. 441–443.</ref> [[wikipedia:Teresa Maryańska|Teresa Maryańska]] and Osmólska also proposed thermoregulation at about the same time,<ref name=MO79>Maryańska, Teresa and Osmólska, Halszka, in 1979. ''Aspects of hadrosaurian cranial anatomy'', from the Journal of Lethaia, vol. 12, on pp. 265–273.</ref> and Sullivan and Williamson took further interest. David Evans' 2006 discussion of lambeosaurine crest functions was favorable to the idea, at least as an initial factor for the evolution of crest expansion.<ref name=DCE06/> |

The large surface area and [[wikipedia:vascularization|vascularization]] of the crest also suggests a thermoregulatory function.<ref name=SW96>Sullivan, Robert M. and Williamson, Thomas E., 1996. A new skull of ''Parasaurolophus'' (long-crested form) from New Mexico: external and internal (CT scans) features and their functional implications, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 16, issue 3, Suppl. pp.68A.</ref> P.E. Wheeler first suggested this use in 1978 as a way keep the brain cool.<ref name=PEW78>Wheeler, P.E., 1978. ''Elaborate CNS cooling structure in large dinosaurs'' Journal of Nature, vol. 275, on pp. 441–443.</ref> [[wikipedia:Teresa Maryańska|Teresa Maryańska]] and Osmólska also proposed thermoregulation at about the same time,<ref name=MO79>Maryańska, Teresa and Osmólska, Halszka, in 1979. ''Aspects of hadrosaurian cranial anatomy'', from the Journal of Lethaia, vol. 12, on pp. 265–273.</ref> and Sullivan and Williamson took further interest. David Evans' 2006 discussion of lambeosaurine crest functions was favorable to the idea, at least as an initial factor for the evolution of crest expansion.<ref name=DCE06/> |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Paleoenvironment== |

||

| ⚫ | ''Parasaurolophus walkeri'', from the [[wikipedia:Dinosaur Park Formation|Dinosaur Park Formation]], was a member of a diverse and well-documented fauna of prehistoric animals, including well-known dinosaurs such as the [[wikipedia:ceratopsidae|horned]] ''[[wikipedia:Centrosaurus|Centrosaurus]]'', ''[[Styracosaurus]]'', and ''[[Chasmosaurus]]''; fellow duckbills ''[[wikipedia:Prosaurolophus|Prosaurolophus]]'', ''[[Gryposaurus]]'', ''[[Corythosaurus]]'', and ''[[Lambeosaurus]]''; [[wikipedia:Tyrannosaurid|tyrannosaurid]] ''[[wikipedia:Gorgosaurus|Gorgosaurus]]''; and [[wikipedia:ankylosauridae|armored]] ''[[Wikipedia:Edmontonia|Edmontonia]]'' and ''[[wikipedia:Euoplocephalus|Euoplocephalus]]''.<ref name=WETAL04/> It was a rare constituent of this fauna.<ref name=RE05/> The Dinosaur Park Formation is interpreted as a low-relief setting of rivers and floodplains that became more swampy and influenced by marine conditions over time as the [[Wikipedia:Western Interior Seaway|Western Interior Seaway]] [[wikipedia:transgression (geology)|transgressed]] westward.<ref name=DAE05>Eberth, David A. 2005. "The geology", in ''Dinosaur Provincial Park'', pp. 54-82.</ref> The climate was warmer than present-day Alberta, without frost, but with wetter and drier seasons. Conifers were apparently the dominant [[wikipedia:forest canopy|canopy]] plants, with an understory of ferns, tree ferns, and [[wikipedia:angiosperm|angiosperms.]]<ref name=BK05>Braman, Dennis R., and Koppelhus, Eva B. 2005. "Campanian palynomorphs", in ''Dinosaur Provincial Park'', pp. 101-130.</ref> |

||

==In the Media== |

==In the Media== |

||

[[File:Image-1.jpg|thumb|220x220px|left|A Parasaurolophus from ''Jurassic World''.]] |

[[File:Image-1.jpg|thumb|220x220px|left|A Parasaurolophus from ''Jurassic World''.]] |

||

| − | * |

+ | *It was in the movie ''Disney's [[Dinosaur (movie)|Dinosaur]]'' as a herd member along with being part of the tie-in ride at [[DinoLand U.S.A.|Dinoland USA]], Disney World by the same name. |

| − | *It also made several appearances in the famous documentary ''Clash of the Dinosaurs''. |

+ | *It also made several appearances in the famous documentary ''[[Clash of the Dinosaurs]]''. |

| − | *It also appeared in the |

+ | *It also appeared in the BBC TV series ''[[Prehistoric Park]]'', where it became the prey of large carnivores ''[[Deinosuchus]] ''and ''[[Albertosaurus]]''. |

| − | *It made a few appearances in all of the Jurassic Park |

+ | *It made a few appearances in all of the Jurassic Park/World movies, as a herd member in the first movie, then some were being held captive by hunters in the second movie and herding with ''[[Corythosaurus]]'' in the third movie, and background dinosaurs in the fourth film and in the fifth film. In [[Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom|Jurassic World Fallen Kingdom]], several ''Parasaurolophus'' were captured and taken to Lockwood Manor to be sold off in auction, but thanks to Owen, Claire, Franklin, Zia and Maisie, they would eventually escape the estate along with the other dinosaurs. In [[Jurassic World: Dominion|Jurassic World Domion]], ''Parasaurolophus'' had a few edits to the head, and the body is a bit bulkier. A small herd is present in the Biosyn Sanctuary in the Dolomite Mountains. |

| − | *The character [ |

+ | *The character [https://were-back-a-dinosaurs-story.fandom.com/wiki/Dweeb Dweeb] in "[[We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story]]," is a ''Parasaurolophus'' himself. Unlike the real, herbivorous animal, Dweeb loves eating hot dogs. |

*''Parasaurolophus'' also appears in ''Turok'', as a docile plant eater that is normally not harmful, but can be aggressive if severely provoked. |

*''Parasaurolophus'' also appears in ''Turok'', as a docile plant eater that is normally not harmful, but can be aggressive if severely provoked. |

||

| Line 109: | Line 106: | ||

*''Parasaurolophus'' appears briefly at the beginning of the Disney Pixar film ''[[The Good Dinosaur]]'', along with a [[Diplodocus]]. |

*''Parasaurolophus'' appears briefly at the beginning of the Disney Pixar film ''[[The Good Dinosaur]]'', along with a [[Diplodocus]]. |

||

| − | *It also appears in Ark Survival Evolved |

+ | *It also appears in Ark Survival Evolved as a docile dinosaur that will never attack the player. |

| − | *The Parasaurolophus appears |

+ | *The Parasaurolophus appears Toy Story That Time Forgot that are the female Battlesaurs. |

*Parasaurolophus is featured in [[The Isle|the isle]] as the third hadrosaur implemented to the game. |

*Parasaurolophus is featured in [[The Isle|the isle]] as the third hadrosaur implemented to the game. |

||

| − | *A bunch of Parasaurolophus was seen in the animated Disney show Gigantosaurus. But among those is a young daring Parasaurolophus named Rocky. |

+ | *A bunch of Parasaurolophus was seen in the animated Disney show [[Gigantosaurus (TV Series)|Gigantosaurus]]. But among those is a young daring Parasaurolophus named Rocky. |

*There were a couple Concepts of a Parasaurolophus for [[Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs]]. The Parasaurolophus was originally planned to appear in the 3rd Ice Age Film, but at the end of the final decision & production it was cut out. |

*There were a couple Concepts of a Parasaurolophus for [[Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs]]. The Parasaurolophus was originally planned to appear in the 3rd Ice Age Film, but at the end of the final decision & production it was cut out. |

||

| + | *Parasaurolophus appeared on [[Dinosaur King]] as one of the main dinosaurs. |

||

| + | *Ariel from [[Dink, the Little Dinosaur|Dink the little dinosaur]] is a leutistic Parasaurolophus. |

||

| + | *Parasaurolophus appeared on [[Dinosaur Train]]. |

||

* The Parasaurolophus appears as a cameo in [[Dino-Riders]]. |

* The Parasaurolophus appears as a cameo in [[Dino-Riders]]. |

||

| − | * Rolf from |

+ | * Rolf from Dinosaur Adventure 3D is a Parasaurolophus. |

| − | *It made an appearance in the Roblox game called "Dinosaur Simulator." |

+ | *It made an appearance in the Roblox game called "[[Dinosaur Simulator (Roblox game)|Dinosaur Simulator]]." |

| + | *''Parasaurolophus'' appears in [[Prehistoric Kingdom]] with skins for ''P. walkeri'' and ''P. cyrtocristatus'' along with close relative and possible species; ''[[Charonosaurus]].'' |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==Gallery== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 133: | Line 131: | ||

* [https://archive.is/20121208200849/skeletaldrawing.com/psgallery/images/parasaurolophuscomparison.jpg Restorations of ''P. walkeri'' and ''P. cyrtocristatus''], to the same scale, by Scott Hartman; at Skeletal Drawing.com. |

* [https://archive.is/20121208200849/skeletaldrawing.com/psgallery/images/parasaurolophuscomparison.jpg Restorations of ''P. walkeri'' and ''P. cyrtocristatus''], to the same scale, by Scott Hartman; at Skeletal Drawing.com. |

||

* [http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/dinosaurs/dinos/Parasaurolophus.shtml ''Parasaurolophus page on Enchanted Learning.com''] |

* [http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/dinosaurs/dinos/Parasaurolophus.shtml ''Parasaurolophus page on Enchanted Learning.com''] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Cretaceous dinosaurs]] |

[[Category:Cretaceous dinosaurs]] |

||

[[Category:Dinosaurs of North America]] |

[[Category:Dinosaurs of North America]] |

||

[[Category:Crested dinosaurs]] |

[[Category:Crested dinosaurs]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Ornithopoda]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Extinct fauna of North America]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric reptiles of North America]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric reptiles of North America]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Cretaceous Period]] |

[[Category:Cretaceous Period]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

[[Category:ARK: Survival Evolved Creatures]] |

[[Category:ARK: Survival Evolved Creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Diapsida]] |

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Famous animals]] |

[[Category:Famous animals]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:The Good Dinosaur Creatures]] |

[[Category:The Good Dinosaur Creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Prehistoric Park Creatures]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric Park Creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Fantasia Creatures]] |

[[Category:Herbivores]] |

[[Category:Herbivores]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Taxa named by William Parks]] |

[[Category:Taxa named by William Parks]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:1922]] |

[[Category:The Land Before Time Creatures]] |

[[Category:The Land Before Time Creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Late Cretaceous]] |

[[Category:Late Cretaceous]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Disney's Dinosaur creatures]] |

[[Category:Disney's Dinosaur creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Dino King]] |

| − | [[Category:Dinosaur Train |

+ | [[Category:Dinosaur Train Creatures]] |

[[Category:We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story creatures]] |

[[Category:We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Transformers creatures]] |

[[Category:Transformers creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Prehistoric Kingdom]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric Kingdom]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Extinct |

+ | [[Category:Extinct fauna of North America]] |

| − | [[Category:Pokemon |

+ | [[Category:Pokemon inspirations]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

[[Category:Carnivores Creatures]] |

[[Category:Carnivores Creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

[[Category:Fantasia Creatures]] |

[[Category:Fantasia Creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| ⚫ | |||

| − | [[Category:Prehistoric reptiles of Asia]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Prehistoric animals of Asia]] |

||

[[Category:Dinosaur Park Formation]] |

[[Category:Dinosaur Park Formation]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Scollard formation]] |

[[Category:Dinosaurs of Canada]] |

[[Category:Dinosaurs of Canada]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Seton Academy Creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Dino-Riders |

+ | [[Category:Dino-Riders]] |

[[Category:Tartakovsky's Primal Creatures]] |

[[Category:Tartakovsky's Primal Creatures]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | [[Category:Dinosaur Train |

+ | [[Category:Dinosaur Train Creatures]] |

| − | [[Category:Walking With |

+ | [[Category:Walking With Franchise]] |

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Fossil Fighters]] |

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Dinosaurs: Fun, Fact and Fantasy creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Clash Of The Dinosaurs creatures]] |

[[Category:Clash Of The Dinosaurs creatures]] |

||

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Creatures of Dinosaur Adventure 3D]] |

||

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:You Are Umasou creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Complete fossils]] |

[[Category:Complete fossils]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Dinosaur Hunting XBOX Creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Gigantosaurus creatures]] |

||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | [[Category:Jurassic Park |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

[[Category:The Isle dinosaurs]] |

[[Category:The Isle dinosaurs]] |

||

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Smithsonian: Dinosaur Playing Cards]] |

||

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Animal Crossing fossils]] |

| − | [[Category: |

+ | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

| − | [[Category:Dino |

+ | [[Category:Dino-Riders]] |

[[Category:King Kong Creatures]] |

[[Category:King Kong Creatures]] |

||

[[Category:The Flintstones Creatures]] |

[[Category:The Flintstones Creatures]] |

||

[[Category:Turok Creatures]] |

[[Category:Turok Creatures]] |

||

| + | |||

| − | [[Category:Dinosaurs from Horseshoe Canyon]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:K/T Extinctions]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Ornithischia]] |

||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Herbivorous Megafauna]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Bipedal]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Quadrupedal]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Cretaceous]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Herbivorous Megafauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Megafauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Jurassic Park]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Megafauna]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Mesozoic Fauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Extinct fauna of North America]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Campanian Fauna]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Maastrichtian Fauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Maastrichtian Reptiles]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Mesozoic Fauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Megafauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Megafauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Dinosauria (web series) animals]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | [[Category:Herbivores]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Extinct Fauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Extinct Fauna]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Dino Pops]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hadrosauridae]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hadrosauria]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hadrosauroidea]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hadrosauromorpha]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Hadrosauriformes]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Lambeosaurinae]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Quadrupedal]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Quadrupedal]] |

||

Latest revision as of 00:43, 6 April 2024

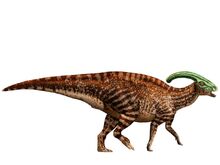

| Parasaurolophus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous | |

|---|---|

| |

| A restoration of Parasaurolophus tubicen by DeadEconomy | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Tribe: | †Parasaurolophini |

| Genus: | †Parasaurolophus Parks, 1922 |

| Type species | |

| †Parasaurolophus walkeri Parks, 1922 | |

| Referred species | |

and see text. | |

| Synonyms | |

and see text. | |

Parasaurolophus (pronounced /ˌpærəsɔˈrɒləfəs/ PARR-ə-saw-ROL-ə-fəs, commonly also /ˌpærəˌsɔrəˈloʊfəs/ PARR-ə-SAWR-ə-LOH-fəs; meaning "near crested lizard" in reference to Saurolophus), commonly shortened as Parasaur, is a genus of ornithopod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now North America, about 83-73 million years ago. It was a herbivore that walked both as a biped and a quadruped. Three species are recognized: P. walkeri (the type species), P. tubicen, and the short-crested P. cyrtocristatus. Remains are known from Alberta, Canada, and New Mexico and Utah, USA. It was first described in 1922 by William Parks from a skull and partial skeleton in Alberta.

Parasaurolophus is a hadrosaurid (commonly referred to as Duck billed dinosaurs because of their mouths resembling the bills of waterfowl such as ducks) part of a diverse family of Cretaceous dinosaurs known for their range of bizarre head adornments. This genus is known for its large, elaborate cranial crest, which at its largest forms a long curved tube projecting upwards and back from the skull. Charonosaurus from China, which may have been its closest relative, had a similar skull and potentially a similar crest. The crest has been much discussed by scientists; the consensus is that major functions included visual recognition of both species and sex, acoustic resonance, and thermoregulation. It is one of the rarer duckbills, being known from only a handful of good specimens.

Description

As is the case with most dinosaurs, the skeleton of Parasaurolophus is incompletely known. The length of the type specimen of P. walkeri is estimated at 9.5 meters (31 ft). Its skull is about 1.6 meters (5.2 ft) long, including the crest, whereas the type skull of P. tubicen is over 2.0 meters (6.6 ft) long, indicating a larger animal.[1] P. walkeri's weight is estimated at 3.6 tonnes (4 tons),P. tubicen is estimated to be 6.6 tonnes (7 tons) and P. cytocristatus ist estimated to be 12.6 tonnes (13 tons).single known forelimb was relatively short for a hadrosaurid, with a short but wide shoulder blade. The thighbone measures 103 centimeters (3.38 ft) long in P. walkeri and is robust for its length when compared to other hadrosaurids.[2] The upper arm and pelvic bones were also heavily built.[3]

Like other hadrosaurids, it was able to walk on either two legs or four. It probably preferred to forage for food on four legs, but ran on two.[4] The neural spines of the vertebrae were tall, as was common in lambeosaurines;[2] tallest over the hips, they increased the height of the back. Skin impressions are known for P. walkeri, showing uniform tubercle-like scales but no larger structures.[5]

The most noticeable feature was the cranial crest, which protruded from the rear of the head and was made up of the premaxilla and nasal bones. The P. walkeri type specimen has a notch in the neural spines near where the crest would hit the back, but this may be a pathology peculiar to this individual.[2] William Parks, who named the genus, hypothesized that a ligament ran from the crest to the notch to support the head.[5] Although the idea seems unlikely,[6] Parasaurolophus is sometimes restored with a skin flap from the crest to the neck.

The crest was hollow, with distinct tubes leading from each nostril to the end of the crest before reversing direction and heading back down the crest and into the skull. The tubes were simplest in P. walkeri, and more complex in P. tubicen, where some tubes were blind and others met and separated.[7] While P. walkeri and P. tubicen had long crests with only slight curvature, P. cyrtocristatus had a short crest with a more circular profile.[8]

Classification

As its name implies, Parasaurolophus was initially thought to be closely related to Saurolophus because of its superficially similar crest.[5] However, it was soon reassessed as a member of the lambeosaurine subfamily of hadrosaurids—Saurolophus is an hadrosaurine.[9] It is usually interpreted as a separate offshoot of the lambeosaurines, distinct from the helmet-crested Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, and Lambeosaurus.[4][10][11] Its closest known relative appears to be Charonosaurus, a lambeosaurine with a similar skull (but no complete crest yet) from the Amur region of northeastern China,[12] and the two may form a clade Parasaurolophini.[11] P. cyrtocristatus, with its short, rounder crest, may be the most basal of the three known Parasaurolophus species,[11] or it may represent subadult or female specimens of P. tubicen.[13]

History

Dicovery and naming

Meaning "near crested lizard", the name Parasaurolophus is derived from the Greek para/παρα "beside" or "near", sauros/σαυρος "lizard" and lophos/λοφος "crest".[14] It is based on ROM 768, a skull and partial skeleton missing most of the tail and the hind legs below the knees, which was found by a field party from the University of Toronto in 1920 near Sand Creek along the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada.[5] These rocks are now known as the Campanian-age Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation. William Parks named the specimen P. walkeri in honor of Sir Byron Edmund Walker, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Ontario Museum.[5] Parasaurolophus remains are rare in Alberta,[15] with only one other partial skull from (probably) the Dinosaur Park Formation,[16] and three Dinosaur Park specimens lacking skulls, possibly belonging to the genus.[17] In some faunal lists, there is a mention of possible P. walkeri material in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, a rock unit of late Maastrichtian age.[18][19] This occurrence is not noted by Sullivan and Williamson in their 1999 review of the genus,[7] and has not been further elaborated upon elsewhere.

In 1921, Charles H. Sternberg recovered a partial skull (PMU.R1250) from what is now known as the slightly younger Kirtland Formation in San Juan County, New Mexico. This specimen was sent to Uppsala, Sweden, where Carl Wiman described it as a second species, P. tubicen, in 1931.[20] The specific epithet is derived from the Latin tǔbǐcěn "trumpeter".[21] A second, nearly complete P. tubicen skull (NMMNH P-25100) was found in New Mexico in 1995. Using computed tomography of this skull, Robert Sullivan and Thomas Williamson gave the genus a monographic treatment in 1999, covering aspects of its anatomy and taxonomy, and the functions of its crest.[7] Williamson later published an independent review of the remains, disagreeing with the taxonomic conclusions.[13]

John Ostrom described another good specimen (FMNH P27393) from New Mexico as P. cyrtocristatus in 1961. It includes a partial skull with a short, rounded crest, and much of the postcranial skeleton except for the feet, neck, and parts of the tail.[8] Its specific name is derived from the Latin curtus "shortened" and cristatus "crested".[21] The specimen was found in either the top of the Fruitland Formation or, more likely, the base of the overlying Kirtland Formation.[7] The range of this species was expanded in 1979, when David B. Weishampel and James A. Jensen described a partial skull with a similar crest (BYU 2467) from the Campanian-age Kaiparowits Formation of Garfield County, Utah.[22] Since then, another skull has been found in Utah with the short/round P. cyrtocristatus crest morphology.[7]

Species

The type species P. walkeri, from Alberta, is known from a single specimen.[4] It differs from P. tubicen by having simpler tubes in its crest,[7] and from P. cyrtocristatus by having a long, unrounded crest and a longer upper arm than forearm.[8]

P. tubicen, from New Mexico, is known from the remains of at least three individuals.[4] It is the largest species, with more complex air passages in its crest than P. walkeri, and a longer, straighter crest than P. cyrtocristatus.[7]

P. cyrtocristatus, from New Mexico and Utah, is known from three possible specimens. It is the smallest species, with a short rounded crest.[7] Its small size and the form of its crest have led several scientists to suggest that it represents juveniles or females of P. tubicen, which is from roughly the same time and from the same formation in New Mexico. As noted by Thomas Williamson, the type material of P. cyrtocristatus is about 72% the size of P. tubicen, close to the size at which other lambeosaurines are interpreted to begin showing definitive sexual dimorphism in their crests (~70% of adult size).[13] This position has been rejected in recent reviews of lambeosaurines.[4][11] In January 25, 2021, a well-preserved skull of Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus was founded and reveals the dinosaur evolution of bizarre crest.

Paleobiology

The New Mexican species shared their environment with the duckbill Kritosaurus, horned Pentaceratops, armored Nodocephalosaurus, Saurornitholestes, and currently unnamed tyrannosaurids.[19] The Kirtland Formation is interpreted as river floodplains appearing after a retreat of the Western Interior Seaway. Conifers were the dominant plants, and chasmosaurine horned dinosaurs were apparently more common than hadrosaurids.[23]

Feeding

As a hadrosaurid, Parasaurolophus was a large bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore, eating plants with a sophisticated skull that permitted a grinding motion analogous to chewing. Its teeth were continually replacing and packed into dental batteries that contained hundreds of teeth, only a relative handful of which were in use at any time. It used its beak to crop plant material, which was held in the jaws by a cheek-like organ. Feeding would have been from the ground up to around 4 meters (13 feet) above.[4] As noted by Bob Bakker, lambeosaurines have narrower beaks than hadrosaurines, implying that Parasaurolophus and its relatives could feed more selectively than their broad-beaked, crestless counterparts.[24]

Cranial crest

Inner Crest Tubes

Many hypotheses have been advanced as to what functions the cranial crest of Parasaurolophus performed, but most have been discredited.[6][25] It is now believed that it may have had several functions: visual display for identifying species and sex, sound amplification for communication, and thermoregulation. It is not clear which was most significant at what times in the evolution of the crest and its internal nasal passages.[26]

Differences between species and growth stages

Skull differences between female (A) & male (B).

As for other lambeosaurines, it is believed that the cranial crest of Parasaurolophus changed with age and was a sexually dimorphic characteristic in adults. James Hopson, one of the first researchers to describe lambeosaurine crests in terms of such distinctions, suggested that P. cyrtocristatus, with its small crest, was the female form of P. tubicen.[27] Thomas Williamson suggested it was the juvenile form.[13] Neither hypothesis became widely accepted. As only six good skulls and one juvenile braincase are known, additional material will help clear up these potential relationships. Williamson noted that in any case, juvenile Parasaurolophus probably had small, rounded crests like P. cyrtocristatus, that probably grew faster as individuals approached maturity.[13] Recent restudy of a juvenile braincase previously assigned to Lambeosaurus, and now assigned to Parasaurolophus, provides evidence that a small tubular crest was present in juveniles. This specimen preserves a small upward flaring of the frontal bones that was similar to but smaller than what is seen in adult specimens; in adults, the frontals formed a platform that supported the base of the crest. This specimen also indicates that the growth of the crest in Parasaurolophus and the facial profile of juvenile individuals differed from the Corythosaurus-Hypacrosaurus-Lambeosaurus model, in part because the crest of Parasaurolophus lacks the thin bony 'coxcomb' that makes up the upper portion of the crest of the other three lambeosaurines.[16]

Rejected hypotheses about function

Many early suggestions focused on adaptations for an aquatic lifestyle, following the hypothesis that hadrosaurids were amphibious, a common line of thought until the 1960s. Thus, Alfred Sherwood Romer proposed it served as a snorkel,[28] Martin Wilfarth that it was an attachment for a mobile proboscis used as a breathing tube or for food gathering,[29] Charles M. Sternberg that it served as an airtrap to keep water out of the lungs,[30] and Ned Colbert that it served as an air reservoir for prolonged stays underwater.[31]

Other proposals were more physical in nature. As mentioned above, William Parks suggested that it was joined to the vertebrae with ligaments or muscles, and helped with moving and supporting the head.[5] Othenio Abel proposed it was used as a weapon in combat among members of the same species,[32] and Andrew Milner suggested that it could be used as a foliage deflector, like the helmet crest (called a 'casque') of the cassowary.[25] Still other proposals made housing specialized organs the major function. Halszka Osmólska suggested that it housed salt glands,[33] and John Ostrom suggested that it housed expanded areas for olfactory tissue and much improved sense of smell of the lambeosaurines, which had no obvious defensive capabilities.[34] One unusual suggestion, made by creationist Duane Gish, is that the crest housed chemical glands that allowed it to throw jets of chemical "fire" at enemies, similar to the modern-day bombardier beetle.[35]

Most of these hypotheses have been discredited or rejected.[6] For example, there is no hole at the end of the crest for a snorkeling function. There are no muscle scars for a proboscis and it is dubious that an animal with a beak would need one. As a proposed airlock, it would not have kept out water. The proposed air reservoir would have been insufficient for an animal the size of Parasaurolophus. Other hadrosaurids had large heads without needing large hollow crests to serve as attachment points for supporting ligaments.[34] Also, none of the proposals explain why the crest has such a shape, why other lambeosaurines should have crests that look much different but perform a similar function, how crestless or solid-crested hadrosaurids got along without such capabilities, or why some hadrosaurids had solid crests. These considerations particularly impact hypotheses based on increasing the capabilities of systems already present in the animal, such as the salt gland and olfaction hypotheses,[25] and indicate that these were not primary functions of the crest. Additionally, work on the nasal cavity of lambeosaurines shows that olfactory nerves and corresponding sensory tissue were largely outside the portion of the nasal passages in the crest, so the expansion of the crest had little to do with the sense of smell.[26]

Social functions

Instead, social and physiological functions have become more supported as function(s) of the crest, focusing on visual and auditory identification and communication. As a large object, the crest has clear value as a visual signal, and sets this animal apart from its contemporaries. The large size of hadrosaurid eye sockets and the presence of sclerotic rings in the eyes imply acute vision and diurnal habits, evidence that sight was important to these animals. If, as is commonly illustrated, a skin frill extended from the crest to the neck or back, the proposed visual display would have been much showier.[27] As is suggested by other lambeosaurine skulls, the crest of Parasaurolophus likely permitted both species identification (such as separating it from Corythosaurus or Lambeosaurus) and determination between males and females, based on shape and size.[26]

Sounding function

However, the external appearance of the crest does not correspond to the complex internal anatomy of the nasal passages, which suggests another function accounted for usage of the internal space.[26] Carl Wiman was the first to propose, in 1931, that the passages served an auditory signaling function, like a crumhorn;[20] Hopson and David B. Weishampel revisited this idea in the 1970s and 1980s.[27][36][37] Hopson found that there is anatomical evidence that hadrosaurids had strong hearing. There is at least one example, in the related Corythosaurus, of a slender stapes (reptilian ear bone) in place, which combined with a large space for an eardrum implies a sensitive middle ear. Furthermore, the hadrosaurid lagena is elongate like a crocodilian's, indicating that the auditory portion of the inner ear was well-developed.[27] Weishampel suggested that P. walkeri was able to produce frequencies of 48 to 240 Hz, and P. cyrtocristatus (interpreted as a juvenile crest form) 75 to 375 Hz. Based on similarity of hadrosaurid inner ears to those of crocodiles, he also proposed that adult hadrosaurids were sensitive to high frequencies, such as their offspring might produce. According to Weishampel, this is consistent with parents and offspring communicating.[36]

Computer modeling of a well-preserved specimen of P. tubicen, with more complex air passages than those of P. walkeri, has allowed the reconstruction of the possible sound its crest produced.[38] The main path resonates at around 30 Hz, but the complicated sinus anatomy causes peaks and valleys in the sound.[39]

Cooling function

The large surface area and vascularization of the crest also suggests a thermoregulatory function.[40] P.E. Wheeler first suggested this use in 1978 as a way keep the brain cool.[41] Teresa Maryańska and Osmólska also proposed thermoregulation at about the same time,[42] and Sullivan and Williamson took further interest. David Evans' 2006 discussion of lambeosaurine crest functions was favorable to the idea, at least as an initial factor for the evolution of crest expansion.[26]

Paleoenvironment

Parasaurolophus walkeri, from the Dinosaur Park Formation, was a member of a diverse and well-documented fauna of prehistoric animals, including well-known dinosaurs such as the horned Centrosaurus, Styracosaurus, and Chasmosaurus; fellow duckbills Prosaurolophus, Gryposaurus, Corythosaurus, and Lambeosaurus; tyrannosaurid Gorgosaurus; and armored Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus.[19] It was a rare constituent of this fauna.[15] The Dinosaur Park Formation is interpreted as a low-relief setting of rivers and floodplains that became more swampy and influenced by marine conditions over time as the Western Interior Seaway transgressed westward.[43] The climate was warmer than present-day Alberta, without frost, but with wetter and drier seasons. Conifers were apparently the dominant canopy plants, with an understory of ferns, tree ferns, and angiosperms.[44]

In the Media

A Parasaurolophus from Jurassic World.

- It was in the movie Disney's Dinosaur as a herd member along with being part of the tie-in ride at Dinoland USA, Disney World by the same name.

- It also made several appearances in the famous documentary Clash of the Dinosaurs.

- It also appeared in the BBC TV series Prehistoric Park, where it became the prey of large carnivores Deinosuchus and Albertosaurus.

- It made a few appearances in all of the Jurassic Park/World movies, as a herd member in the first movie, then some were being held captive by hunters in the second movie and herding with Corythosaurus in the third movie, and background dinosaurs in the fourth film and in the fifth film. In Jurassic World Fallen Kingdom, several Parasaurolophus were captured and taken to Lockwood Manor to be sold off in auction, but thanks to Owen, Claire, Franklin, Zia and Maisie, they would eventually escape the estate along with the other dinosaurs. In Jurassic World Domion, Parasaurolophus had a few edits to the head, and the body is a bit bulkier. A small herd is present in the Biosyn Sanctuary in the Dolomite Mountains.

- The character Dweeb in "We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story," is a Parasaurolophus himself. Unlike the real, herbivorous animal, Dweeb loves eating hot dogs.

- Parasaurolophus also appears in Turok, as a docile plant eater that is normally not harmful, but can be aggressive if severely provoked.

- There is also a Parasaurolophus zord in Power Rangers: Dino Thunder and Power Rangers: Dino Charge.

- Parasaurolophus appears briefly at the beginning of the Disney Pixar film The Good Dinosaur, along with a Diplodocus.

- It also appears in Ark Survival Evolved as a docile dinosaur that will never attack the player.

- The Parasaurolophus appears Toy Story That Time Forgot that are the female Battlesaurs.

- Parasaurolophus is featured in the isle as the third hadrosaur implemented to the game.

- A bunch of Parasaurolophus was seen in the animated Disney show Gigantosaurus. But among those is a young daring Parasaurolophus named Rocky.

- There were a couple Concepts of a Parasaurolophus for Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs. The Parasaurolophus was originally planned to appear in the 3rd Ice Age Film, but at the end of the final decision & production it was cut out.

- Parasaurolophus appeared on Dinosaur King as one of the main dinosaurs.

- Ariel from Dink the little dinosaur is a leutistic Parasaurolophus.

- Parasaurolophus appeared on Dinosaur Train.

- The Parasaurolophus appears as a cameo in Dino-Riders.

- Rolf from Dinosaur Adventure 3D is a Parasaurolophus.

- It made an appearance in the Roblox game called "Dinosaur Simulator."

- Parasaurolophus appears in Prehistoric Kingdom with skins for P. walkeri and P. cyrtocristatus along with close relative and possible species; Charonosaurus.

References

- ↑ Lull, Richard Swann Wright, Nelda E. Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America, page 229. Published: 1942, Geological Society of America, Geological Society of America Special Paper 40

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Lull and Wright, Hadrosaurian Dinosaurs of North America, pp. 209-213.

- ↑ Brett-Surman, Michael K. and Wagner, Jonathan R. Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.) Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs, chapter: Appendicular anatomy in Campanian and Maastrichtian North American hadrosaurids, pages 135–169. Published, 2006, Indiana University Press, in Bloomington and Indianapolis ISBN 0-253-34817-X

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Horner, John R., Weishampel, David B.; and Forster, Catherine A, Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; and Dodson, Peter (eds.) The Dinosauria, 2nd edition, chapter: Hadrosauridae, pages 438-463. Published: 2004, University of California Press, in Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-24209-2

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Parks, William A. Parasaurolophus walkeri, a new genus and species of crested trachodont dinosaur, volume 13, pages 1-32. Published: 1922, University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Glut, Donald F. Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia, Chapter: Parasaurolophus, pages 678–684. Published: 1997, McFarland & Co, in Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 0-89950-917-7

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Sullivan, Robert M. and Williamson, Thomas E. A new skull of Parasaurolophus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus, from the series New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 15, pages 1-52. Published: 1999, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, in Albuqueque, New Mexico.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ostrom, John H. 1961 A new species of hadrosaurian dinosaur from the Cretaceous of New Mexico, Journal of Paleontology, Volume 35, 3rd issue, on pages 575–577.

- ↑ Gilmore, Charles W., On the genus Stephanosaurus, with a description of the type specimen of Lambeosaurus lambei, volume 38, issue 43, pages 29-48, Parks. Published: 1924, Canada Department of Mines Geological Survey Bulletin (Geological Series)

- ↑ Weishampel, David B. and Horner, Jack R., Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; and Dodson, Peter (eds.) The Dinosauria, 1st edition, Chapter: Hadrosauridae, pages 534-561. Published: 1990, University of California Press in Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-06727-4

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Evans, David C., and Reisz, Robert R. 2007. Anatomy and relationships of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus, a crested hadrosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 27 issue 2, on pages 373–393. [1]

- ↑ Godefroit, Pascal, Shuqin Zan; and Liyong Jin. 2000. Charonosaurus jiayinensis n. g., n. sp., a lambeosaurine dinosaur from the Late Maastrichtian of northeastern China, from the Compte Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences, Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes, vol. 330, pages 875–882.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Williamson, Thomas E. 2000. Review of Hadrosauridae (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the San Juan Basin, New Mexico Lucas, S.G.; and Heckert, A.B. (eds.) Dinosaurs of New Mexico, from the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 17 Published by New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, in Albuqueque, New Mexico. Pages 191–213.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott, 1980. A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition) Published: Oxford University Press in the United Kingdom. ISBN 0-19-910207-4

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ryan, Michael J. and Evans, David C., Currie, Phillip J., and Koppelhus, Eva (eds.). Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed, Chapter: Ornithischian Dinosaurs. 2005, Published: Indiana University Press, in Bloomington. Pages 312–348, ISBN 0-253-34595-2

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Evans, David C., Reisz, Robert R.; and Dupuis, Kevin, 2007. A juvenile Parasaurolophus braincase from Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, with comments on crest ontogeny in the genus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 27, issue 3 pages 642–650.

- ↑ Currie, Phillip J; and Russell, Dale A. "Geographic and stratigraphic distribution of dinosaur remains" in Dinosaur Provincial Park, p. 553.

- ↑ Weishampel, David B. (1990). "Dinosaur Distribution", in The Dinosauria (1st), pp. 63–139.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth, M.P.; and Noto, Christopher R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution", in The Dinosauria (2nd), pp. 517–606.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Wiman, Carl, 1931. Parasaurolophus tubicen, n. sp. aus der Kreide in New Mexico, from the Nova Acta Regia Societas Scientarum Upsaliensis, series 4, vol. 7, issue 5. (German). Pages 1–11.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Simpson, D.P. Cassell's Latin Dictionary, published by Cassell Ltd. 1979, edition 5, in London. ISBN 0-304-52257-0 Page 883.

- ↑ Weishampel, David B. and Jensen, James A. 1979. Parasaurolophus (Reptilia: Hadrosauridae) from Utah, from the Journal of Paleontology, vol. 53, issue 6, pages 1422–1427.

- ↑ Russell, Dale A. An Odyssey in Time: Dinosaurs of North America, 1989. Publisher: NorthWord Press, in Minocqua, Wisconsin. ISBN 1-55971-038-1 Pages 160–164.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction, published by William Morrow, in New York. ISBN 0-8217-2859-8 Page 194.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Norman David B. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: An Original and Compelling Insight into Life in the Dinosaur Kingdom, chapter: Hadrosaurids II. 1985. Published by Crescent Books, in New York. Pages 122–127. ISBN 0-517-468905

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Evans, David C., 2006. Nasal cavity homologies and cranial crest function in lambeosaurine dinosaurs, from the Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 32, issue 1, Pages 109–125. [2]

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Hopson, James A. 1975. The evolution of cranial display structures in hadrosaurian dinosaurs , from the Journal of Paleobiology, volume one, issue one, pages 21–43.

- ↑ Romer. Alfred Sherwood, 1933. Vertebrate Paleontology, from the University of Chicago Press, on page 491.

- ↑ Wilfarth, Martin, 1947. Russeltragende Dinosaurier, from the Journal of Orion (Munich), vol. 2. pp. 525–532 (German language).

- ↑ Sternberg, Charles M. 1935. Hooded hadrosaurs of the Belly River Series of the Upper Cretaceous from the Journal of the Canada Department of Mines Bulletin (Geological Series), volume 77, issue 52, on pages 1–37.

- ↑ Colbert, Edwin H. The Dinosaur Book: The Ruling Reptiles and their Relatives, published in 1945 by the American Museum of Natural History, Man and Nature Publications, 14, in New York. Page 156.

- ↑ Abel, Othenio, 1924. Die neuen Dinosaurierfunde in der Oberkreide Canadas from the Journal of Jarbuch Naturwissenschaften, volume 12, issue 36, on pages 709–716. (German) 1924.

- ↑ Osmólska, Halszka, 1979. Nasal salt glands in dinosaurs, from the Journal of Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, vol. 24, pages 205–215.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Ostrom, John H., 1962. The cranial crests of hadrosaurian dinosaurs, from the Journal of Postilla, vol. 62, pages 1–29.

- ↑ Gish, Duane T., 1992. Dinosaurs by Design, published by Master Books, in Green Forest. ISBN 0-89051-165-9 Page 82.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Weishampel, David B., 1981. Acoustic analyses of potential vocalization in lambeosaurine dinosaurs (Reptilia:Ornithischia), from the Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 7, issue 2, pp. 252–261.

- ↑ Weishampel David B., 1981. The nasal cavity of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids (Reptilia:Ornithischia): comparative anatomy and homologies, from the Journal of Paleontology, vol. 55, issue 5, pp. 1046–1057.

- ↑ Scientists Use Digital Paleontology to Produce Voice of Parasaurolophus Dinosaur, by the Sandia National Laboratories (1997-12-05). Retrieved on January 20th, 2009.

- ↑ Diegert, Carl F. and Williamson, Thomas E., 1998. A digital acoustic model of the lambeosaurine hadrosaur Parasaurolophus tubicen from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 18, issue 3, Suppl. p. 38A.

- ↑ Sullivan, Robert M. and Williamson, Thomas E., 1996. A new skull of Parasaurolophus (long-crested form) from New Mexico: external and internal (CT scans) features and their functional implications, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 16, issue 3, Suppl. pp.68A.

- ↑ Wheeler, P.E., 1978. Elaborate CNS cooling structure in large dinosaurs Journal of Nature, vol. 275, on pp. 441–443.

- ↑ Maryańska, Teresa and Osmólska, Halszka, in 1979. Aspects of hadrosaurian cranial anatomy, from the Journal of Lethaia, vol. 12, on pp. 265–273.

- ↑ Eberth, David A. 2005. "The geology", in Dinosaur Provincial Park, pp. 54-82.

- ↑ Braman, Dennis R., and Koppelhus, Eva B. 2005. "Campanian palynomorphs", in Dinosaur Provincial Park, pp. 101-130.

External links

- Scientists Use Digital Paleontology to Produce Voice of Parasaurolophus Dinosaur; from Sandia National Laboratories.

- Restorations of P. walkeri and P. cyrtocristatus, to the same scale, by Scott Hartman; at Skeletal Drawing.com.

- Parasaurolophus page on Enchanted Learning.com